The Validation of Sterilization-in-Place (SIP) Processes

When process equipment reaches commercial-scale proportions, the sterilization of essential units by autoclaving becomes impractical and some means of sterilizing the equipment in situ is needed. Such installations, in order to comply with cGMP, must be design, installation, and operationally qualified (DQ, IQ, and OQ) and the sterilization process must be validated. So, here is a short introduction to the SIP validation procedure.

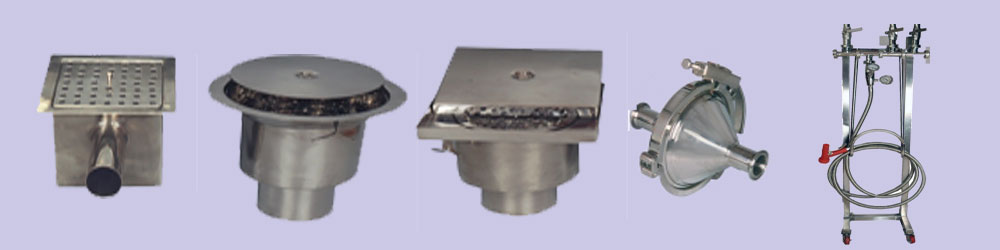

SIP installations will usually comprise one or more pieces of processing equipment, such as a fermentor and a centrifugal separator to handle harvests, connected by rigid stainless steel or flexible Teflon®-lined piping. The installation will be capable of withstanding steam pressure up to, say, 20 psi and corresponding sterilizing temperatures in the 121° to 125°C range. There will be a supply of steam suitable for the procedure, under pressure control, and a "trapped" drain at a low point on the system, which will pass condensed water, but not steam. Suitable safety valves or "burst disks" will control the safe operation of the installation.

Design qualification of a SIP installation will require confirmation that the process equipment, pipe work, and steam supply equipment meet preset specifications for materials and for pressure and temperature resistance. Attention must be paid to the quality of the steam which will be used. This usually means that the steam is generated in a dedicated "clean-steam" generator. The steam may also pass a micro-filter before use. The cleanliness of the steam must be maintained by the use of pressure-grade stainless steel or Teflon®-lined tubing and suitably constructed pressure control and shut-off valves and pressure gauges.

Other design aspects of the equipment intended for SIP will include ensuring that the steam can reach all parts of the equipment in contact with product and that air is not trapped in the plant during sterilization. There must also be a means for the easy clearance of condensate during the heating process, through the steam trap. Finally, temperature sensors must be sited where they will represent reliably the state of the equipment during the sterilization cycle. Often, the most favored point for temperature measurement is at the condensate drain, since this will be the last area to reach operating temperature. However, there may be good reasons for siting thermo-sensors in difficult-to-reach areas of the plant.

Installation qualification of a well-designed SIP system will involve confirming the proper installation of the process equipment and correct siting and connections for all pipe work, including ensuring that proper condensate drainage can occur.

All required services and monitoring devices should be in place. Operational qualification starts with the start-up of the steam generation set-up and confirmation that correct pressure and steam volume is achieved. The sterilizing cycle is then run. Steam under pressure is passed through the entire installation while allowing the escape of air through properly placed vents in the piping or on the equipment. Steam-resistant bacterial filters usually protect these vents. After a suitable period of steaming, the air vents are closed and steam pressure is allowed to build to the required level. Pressure is maintained during a preset period, then the steam is released through a condenser. Temperature sensors in the system should indicate that the recorded pressure resulted in the required temperature being reached for sufficient time to ensure destruction of all contaminants. Cooling down of the equipment requires that air be allowed to pass back into the system through one or more of the sterilizing filters on the vents, to prevent the development of a vacuum.

Validation of the system operations will require the use of chemical and biological indicators, which should be placed in sections of the plant determined to be difficult to free of air, and near the condensate drain. The prescribed sterilization cycle should always yield sterile indicators. The process can be challenged by "worst-case" conditions, such as a reduction in sterilization period or steam pressure. Eventually, a set of operating conditions that have been shown to produce sterile plant reproducibly can be adopted as the validated process. Minimum and maximum limits on the steam pressure, indicated temperature, and exposure time will be set. If appropriate, the final evidence of the validity of the sterilization process may be achieved by running culture medium through the sterilized set up in imitation of the manufacturing processes and then incubating a large number of media samples, or the entire batch, to ensure no bacterial growth occurs. In any event, the regular manufacture of product batches that pass sterility and endotoxin tests after processing in the SIP plant will confirm PQ of the system. These records, however, will not substitute for proper SIP process validation.

Like all validation procedures, the DQ, IQ, and OQ of the system, as well as the validation run parameters and test results, must be fully documented. Measurement devices must be properly calibrated in reference to an accepted standard. If sections of the plant are rebuilt or changed, the entire SIP set up must be revalidated. Given the critical nature of the SIP procedure, it is probably a good idea to schedule revalidation of the installation at regular intervals anyway.